When Ashton Carter takes the oath of office as the US secretary of defense, he will be caught on the horns of an excruciating dilemma. If unresolved, the long-term consequence will be a 21st century replay of the “hollow force” that arose after the Vietnam War ended. That force was unready and largely incapable of carrying out all its duties to defend the nation.

When Ashton Carter takes the oath of office as the US secretary of defense, he will be caught on the horns of an excruciating dilemma. If unresolved, the long-term consequence will be a 21st century replay of the “hollow force” that arose after the Vietnam War ended. That force was unready and largely incapable of carrying out all its duties to defend the nation.

The first and very visible horn of this dilemma is White House guidance. One of many reasons why Carter was chosen for the post is that he is highly experienced, hence a “safe pair of hands” who is unlikely to do “stupid stuff.”

One of Carter’s major tasks will be to oversee the continuing transition of the US military after two highly costly and unwinnable wars to an uncertain environment that will test the Obama administration’s last two years in office.

And he must manage that transition at a time when relations between both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue are contentious at best and probably will worsen. That is a full-time job alone.

The second and invisible horn of his dilemma is the need to transform rather than transition the Pentagon to its next incarnation. Here, the Gordian knot binding the unresolved and possibly unresolvable complex contradictions of a colossal strategy-force structure-budget-cost growth mismatch must be severed.

But no secretary, no matter how competent or skilled, has the authority to wield a sword strong enough to cut this knot. And a real transformation requires an understanding and precise definition of the outcome to be achieved by that process.

In 2001, then-Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld was directed by President George W. Bush to “transform” the Pentagon for the 21st century. But no one could define what was meant by “transformation.”

Frustration on the part of the senior military was so great that in the summer of 2001, the press was filled with rumors that the new secretary’s days were numbered because of alleged indecision and uncertainty on his part in pushing transformation. Of course, Sept. 11 changed that.

Today, the strategic and operationally critical questions Carter should address pertain to the rationale and expectations over what the US military can and cannot accomplish in defending the nation and how to deal with the reality that in the past two wars, the most powerful forces in the world could not defeat enemies that lacked traditional armies, navies and air forces.

The critical management question is how to cope with the surging cost growth across all sectors of the Pentagon, especially pertaining to pay, allowances, health care, retirement, overhead and, of course, weapon systems that, if unchecked, will create this hollow force.

Because the Pentagon is the best-resourced and most capable branch of the US government and infused with a “can-do” spirit, it is invariably the default setting for White Houses to employ when no one else can do the job.

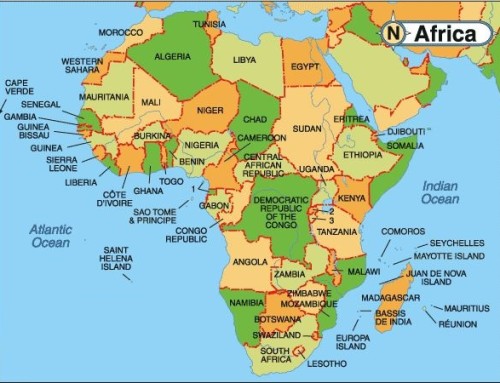

In Iraq and Afghanistan, the US (and allied) militaries were tasked with nation-building as the other arms of government lacked the capacity and capability. As Ebola spread throughout West Africa, the US military sent some 5,000 of its finest to support the medical effort to stem the epidemic. And it was US Navy ships that were deployed in the search for missing airliners in Southeast Asia.

This use of military forces in non-military roles would seem a growth industry given the absence of alternatives.

What then can or should the new secretary do? Leading this transition is more than full-time employment. Add a plethora of current and future crises, days are simply not long enough. And any major transformation effort will drain what is left of the department’s stamina and resources.

The solution to prevent a hollow force from reoccurring must include containing the exploding cost growth, which will break the bank before the end of this decade, while also moving to a smaller, highly capable and ready force that can be maintained at realistic future levels of defense spending, in current dollars, of between $450 billion-$500 billion a year.

Of course, the nation may choose, even inadvertently, to keep a larger, hollower force that could be rebuilt if needed.

While a hollow force sufficed during the Cold War against a definable Soviet threat that could be deterred by nuclear weapons, that world no longer exists. In today’s world, maintaining a flexible, adaptive and capable force must be the goal even if that force is smaller in size. We will see which course the new secretary sets.

Leave A Comment